Energy Flow in Ecosystem: Food Chain & Food Web

Content

- Introduction

- What is an ecosystem?

- Why energy flow matters

- Food chains

- Trophic levels

- The 10% rule

- Food webs

- FAQs

Introduction

Energy flow in ecosystems traces how energy captured from sunlight moves through living organisms from green plants right up to top predators, while steadily decreasing at each step, shaping the very structure of nature’s food networks.

What is an ecosystem?

Think of an ecosystem as nature’s self-contained workshop. It’s a complete community where plants, animals, insects, birds even tiny soil microbes, all live and work together while constantly exchanging energy and materials with their physical surroundings like soil, water, sunlight, and minerals.

A tropical forest covering thousands of square kilometers represents a massive ecosystem. But so does a tiny lily pond in someone’s backyard where frogs, dragonflies, water plants, and fish create their own miniature world of interactions. The size doesn’t matter what counts are the ongoing relationships and energy exchanges happening within that space.

Why energy flow matters

Without a steady supply of energy, no ecosystem could survive even for a day. Every creature needs energy to grow, move, reproduce, and simply stay alive.

This energy doesn’t appear magically, it flows through the system in one direction only, starting with the sun’s rays and passing from plant to animal to microbe.

Understanding this flow helps explain why ecosystems remain balanced, why certain animals dominate particular habitats, and why sudden changes like deforestation or pollution can collapse entire food networks.

The sun as nature’s powerhouse

For nearly every ecosystem on Earth, the sun stands as the ultimate energy source. Its light pours down continuously, and green plants, algae floating in ponds, and even some specialized bacteria soak it up through photosynthesis.

They use sunlight, carbon dioxide from the air, and water from the soil to manufacture sugars and starches, their own food. This process traps solar energy in the chemical bonds of organic molecules, transforming it into a form other organisms can actually use.

A fascinating exception exists deep in the oceans around hydrothermal vents, where sunlight never reaches. Here, certain bacteria draw energy directly from chemicals spewing from the Earth’s crust through chemosynthesis, supporting bizarre ecosystems of giant tube worms and eyeless shrimp.

Food chains

- Picture a grassland at dawn. Grass grows tall under the sun. A rabbit nibbles the tender blades. A hawk spots the rabbit and swoops down for its meal.

- Food Chain: Grass → rabbit → hawk.

- Each step represents a transfer of energy packed inside plant tissues or animal flesh. This straight-line sequence where energy passes as one organism consumes another forms a food chain.

These chains don’t just show who eats whom, they reveal how energy and nutrients travel through living systems. Insects munch leaves, fish swallow smaller fish, vultures pick at lion kills. Each link depends utterly on the one before it.

Trophic levels

Every organism occupies a specific position or “rung” on this energy ladder, called a trophic level:

Level 1– Primary Producers (Autotrophs): Green plants, pond algae, phytoplankton drifting in oceans. Through photosynthesis, they create new organic matter from sunlight, forming the foundation holding all the system’s energy.

Level 2– Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Grasshoppers stripping leaves, deer browsing shrubs, zooplankton filtering tiny algae. These plant-eaters convert plant biomass into animal tissue.

Level 3– Secondary Consumers (Carnivores): Frogs snapping insects, spiders trapping flies, wolves hunting deer. They feed on herbivores, concentrating energy into fewer, larger bodies.

Level 4+– Tertiary Consumers (Top Predators): Eagles, lions, sharks, sometimes even humans. These occupy the pyramid’s peak, controlling populations below them.

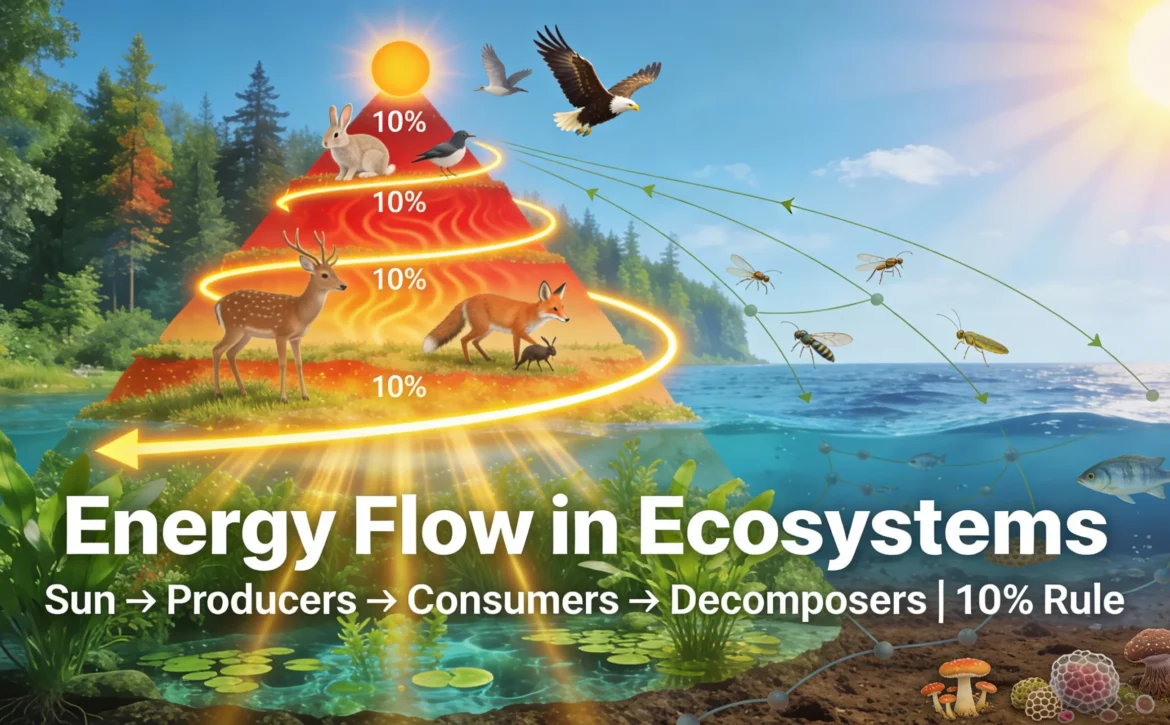

The universal 10% rule

Here’s nature’s iron law: only about 10% of the energy available at one trophic level passes to the next. The other 90% vanishes as heat through respiration, movement, digestion, and basic maintenance. Producers might capture 10,000 units of solar energy. Herbivores receive just 1,000 units from eating plants. Carnivores get a mere 100 units from those herbivores. Top predators scrape by on 10 units.

This massive energy loss explains why food chains rarely extend beyond 4-5 links on land and 6-7 links in water. Beyond that point, insufficient energy remains to support another generation of organisms. Apex predators always represent tiny populations compared to the vast plant masses supporting them.

Food chain patterns

Grazing Food Chains – The sunlight direct route

- Most familiar and energy-rich, these chains begin with living green plants grazed directly by herbivores:

Grass → Grasshopper → Frog → Snake → Hawk - In productive ecosystems like grasslands or coral reefs, enough plant growth exists to sustain this upward energy flow through multiple carnivore levels.

Detritus Food Chains – The recycling route

- These shadowy chains start not with living plants but with dead organic matter like fallen leaves, animal corpses, feces, wood rot.

- Bacteria and fungi attack this detritus first, breaking complex organics into simple nutrients.

- Earthworms, millipedes, and dung beetles feed on this microbial soup, becoming food for birds, lizards, or larger predators:

Dead leaves → Fungi → Millipede → Centipede → Shrew - Detritus chains dominate forest floors and ocean sediments, quietly recycling 80-90% of an ecosystem’s organic matter back into soil nutrients for plants to reuse.

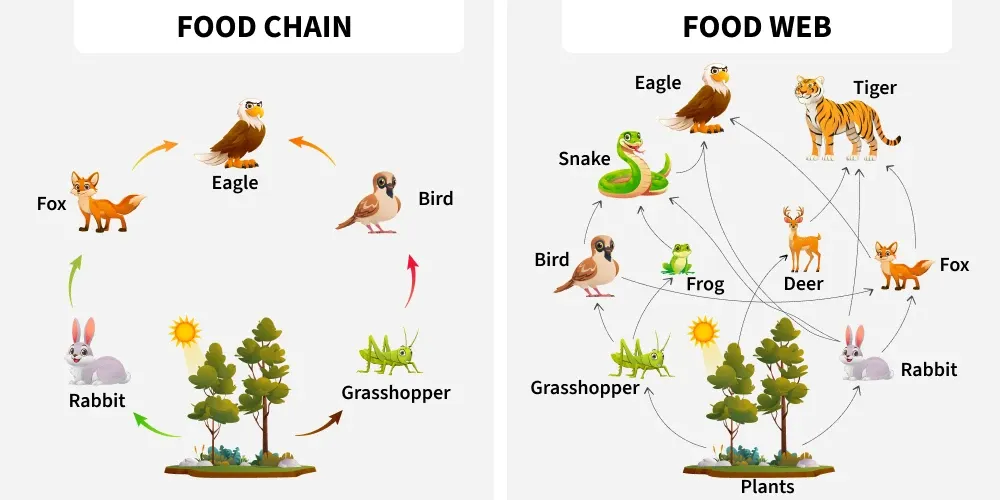

Food webs

Nature abhors straight lines. No rabbit eats only grass, no frog eats solely grasshoppers. A single meadow mouse might munch seeds, insects, and roots while serving as prey for foxes, owls, hawks, and snakes. These interlocking feeding relationships form a food web a complex network of crisscrossing food chains.

Why food webs matter more than chains:

- They show ecosystem resilience. If disease wipes out frogs, energy can still flow through toads or lizards.

- They reveal keystone species whose removal collapses multiple pathways.

- They explain population dynamics why vole outbreaks trigger fox, hawk, and owl population surges simultaneously.

Sunlight remains the base energy source. Producers convert it into organic molecules that ripple outward, sustaining the entire web above them through countless consumption pathways.

FAQs

1. What is energy flow in an ecosystem?

Energy flow refers to the transfer of energy from the Sun to producers (plants), then to consumers and decomposers through food chains and food webs. This flow is always unidirectional.

2. Why is the Sun considered the primary source of energy?

Because green plants capture solar energy through photosynthesis and convert it into chemical energy, which supports all trophic levels.

3. What are trophic levels?

Trophic levels are the feeding positions in a food chain, such as producers, primary consumers, secondary consumers, and tertiary consumers.

4. What is a food chain?

A food chain is a linear sequence showing how energy passes from producers to herbivores and then to carnivores.

6. What is a food web?

A food web is a network of interconnected food chains that shows multiple feeding relationships in an ecosystem.

Click on the question to see the Answers