Gorkhaland Statehood demand

Content

- News in Focus

- Historical Background of the Gorkhaland Region

- Evolution of the Demand for Gorkhaland

- GNLF Movement (1980s)

- Recent Agitations

- Why is the Demand

- Article 3

- Arguments in favour and against

- Way Forward

News in Focus (October 2025)

The demand for Gorkhaland statehood has returned to the national spotlight after the Union Government appointed a former Deputy National Security Advisor, Pankaj Kumar Singh, as an interlocutor to hold talks with political leaders from the Darjeeling hills of West Bengal.

The move has triggered political reactions ahead of the upcoming West Bengal Assembly elections.

Historical Background of the Gorkhaland Region

Colonial Roots

- Treaty of Sinchula (1865):

The British annexed Darjeeling and its adjoining areas after the Anglo-Bhutan War. - The region gained economic importance due to:

- Rising global demand for tea (especially after disruptions in China).

- Establishment of tea plantations in Darjeeling hills.

Demographic Changes

- Large-scale migration of Nepali-speaking Gorkhas occurred due to:

- Employment in tea gardens

- Construction of railways, roads, and other infrastructure

- Over time, the Gorkhas became the dominant socio-cultural group in the hills.

Evolution of the Demand for Gorkhaland

Early Phase (1860s–1947)

- The spread of modern education in the 1860s played a key role in the formation of a distinct Nepali linguistic and cultural identity. Demands for a separate administrative unit for Darjeeling were raised periodically in 1907, 1917, and 1929.

- In 1943, the All India Gorkha League (AIGL) was formed to articulate Gorkha political aspirations. After Independence, the AIGL met Jawaharlal Nehru in 1947, demanding a separate province. The issue also found mention in the Constituent Assembly, where Ari Bahadur Gurung, a member from Kalimpong, raised the demand.

- However, in the decades following Independence, the movement lacked sustained mass mobilisation and resurfaced only intermittently.

Mass Mobilisation and the GNLF Movement (1980s)

- The demand gained momentum in the 1980s under the leadership of Subhash Ghisingh, who formed the Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF) and popularised the term Gorkhaland. The movement turned violent, leading to the death of nearly 1,200 people, as per official estimates.

- In 1988, the Left Front government under Jyoti Basu agreed to the creation of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC). It was conceived as a “state within a state”, granting limited autonomy. However, the DGHC lacked legislative powers, which resulted in dissatisfaction and the perception that popular aspirations remained unfulfilled.

- From 1988 to 2005, the DGHC was administered by the GNLF.

From DGHC to GTA: Continuity of Discontent

- In 2007, Bimal Gurung broke away from the GNLF and formed the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM), once again raising the demand for a separate state. Ghisingh resigned in 2008, and Gurung emerged as the principal leader of the movement.

- After prolonged agitation, the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration (GTA) was established in 2011, replacing the DGHC. The GTA administers the Darjeeling and Kalimpong hills and enjoys limited administrative, executive, and financial powers. However, it too lacks legislative authority, which has remained a core grievance, as people have little control over the laws governing them.

- The GJM won the 2012 GTA elections, strengthening its political position. The creation of Telangana in 2013 further fuelled hopes that Gorkhaland could also achieve statehood.

Recent Agitations and Developments

- In 2017, protests erupted against the perceived imposition of the Bengali language in hill schools, where Nepali is the official language. This led to a 104-day shutdown in Darjeeling, severely impacting the local economy and tourism. Although the state government later clarified that Bengali would not be made compulsory, the episode deepened mistrust.

- In 2025, the Centre’s decision to appoint an interlocutor has reopened dialogue. While the GJM welcomed the move, the TMC accused the Centre of politicising the issue.

Why is the Demand for a Separate State Raised?

1. Ethnic, Linguistic and Cultural Identity

Approximately 14 lakh residents of the region speak Nepali and follow customs and traditions distinct from the Bengali majority of West Bengal. Many Gorkhas perceive cultural marginalisation within the state.

2. Discrimination and Economic Exploitation

Gorkhas often feel reduced to second-class citizens, particularly due to the dominance of non-local bureaucrats and business groups. Tea plantation workers continue to receive wages below minimum levels under the Plantation Labour Act, 1951, intensifying economic grievances.

3. Assertion of Indian Gorkha Identity

Across India, Gorkhas are sometimes viewed as foreigners, leading to demands for a distinct Indian Gorkha identity through statehood.

4. Socio-Economic Backwardness

The region suffers from poor infrastructure, limited employment opportunities, declining tea gardens, and inadequate healthcare and higher education facilities.

5. Political Factors

Electoral politics and regional party competition have kept the issue alive, often resulting in unfulfilled promises.

Article 3 of the Indian Constitution: Creation of New States

The demand for Gorkhaland is constitutionally rooted in Article 3 of the Indian Constitution, which empowers Parliament to:

- Form a new State by separation of territory from any State

- Increase or diminish the area of any State

- Alter the boundaries or name of any State

Key Constitutional Features:

- The power lies exclusively with Parliament, not with State Legislatures.

- The President must refer the proposal to the concerned State Legislature (West Bengal) for its views.

- The opinion of the State Legislature is not binding on Parliament.

Arguments in Favour of Statehood

- Supporters argue that statehood would address the identity crisis, bring administration closer to the people (Darjeeling is nearly 600 km from Kolkata), strengthen the bond between the region and the Indian Union, and enable focused regional development.

Arguments Against Statehood

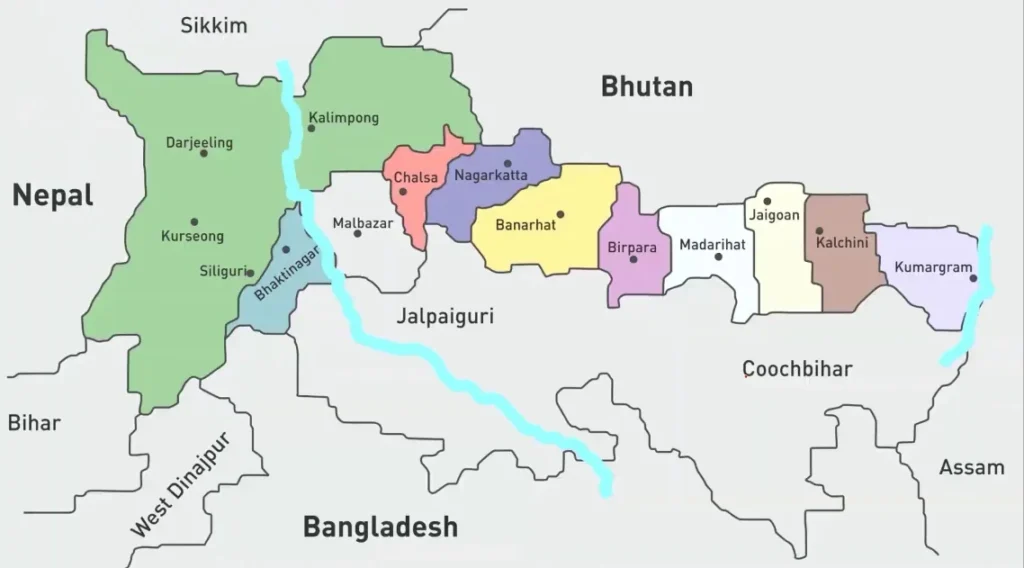

- Opponents cite national security concerns, given the region’s strategic location connecting the Northeast and bordering Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh.

- They also highlight demographic diversity, the small geographical size of the proposed state, the economic loss to West Bengal, past experiences of Bengal’s partition, governance failures of local leadership, and the risk of encouraging similar demands elsewhere.

Way Forward

- While the creation of a separate state does not appear viable in the near future, meaningful governance reforms are essential.

- The West Bengal government must transfer all promised subjects to the GTA, ensure inclusive decision-making, depoliticise the issue, protect cultural and linguistic rights, and address discrimination against Gorkhas across India.

- Confidence-building measures and vigilance against foreign interference are crucial for maintaining regional stability and national integrity.