Interior of the Earth: UPSC Notes

Content

- Introduction

- Sources for the Interior of the Earth

- Structure of the Earth

- Evolution of the Earth’s Layered Structure

- Thermal and Physical State of Earth’s Interior

- Crust

- Mantle

- Core

- FAQs

Introduction

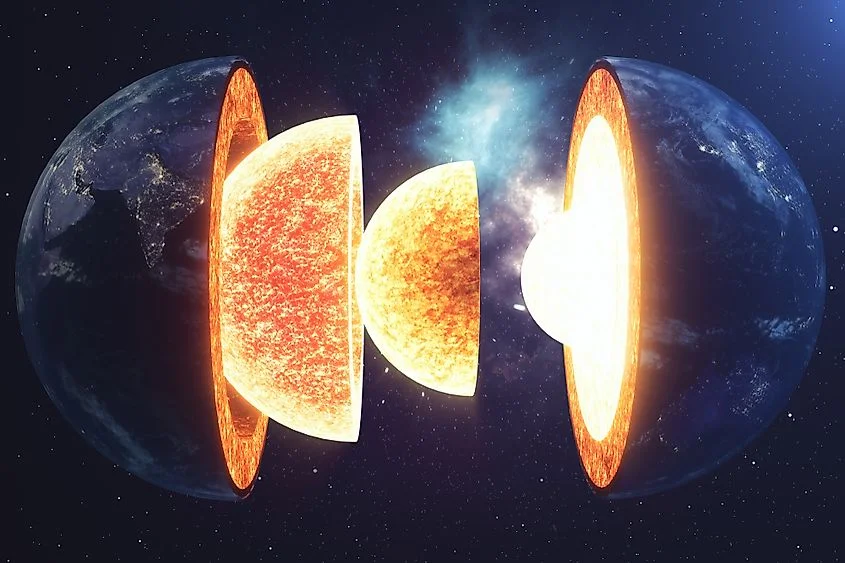

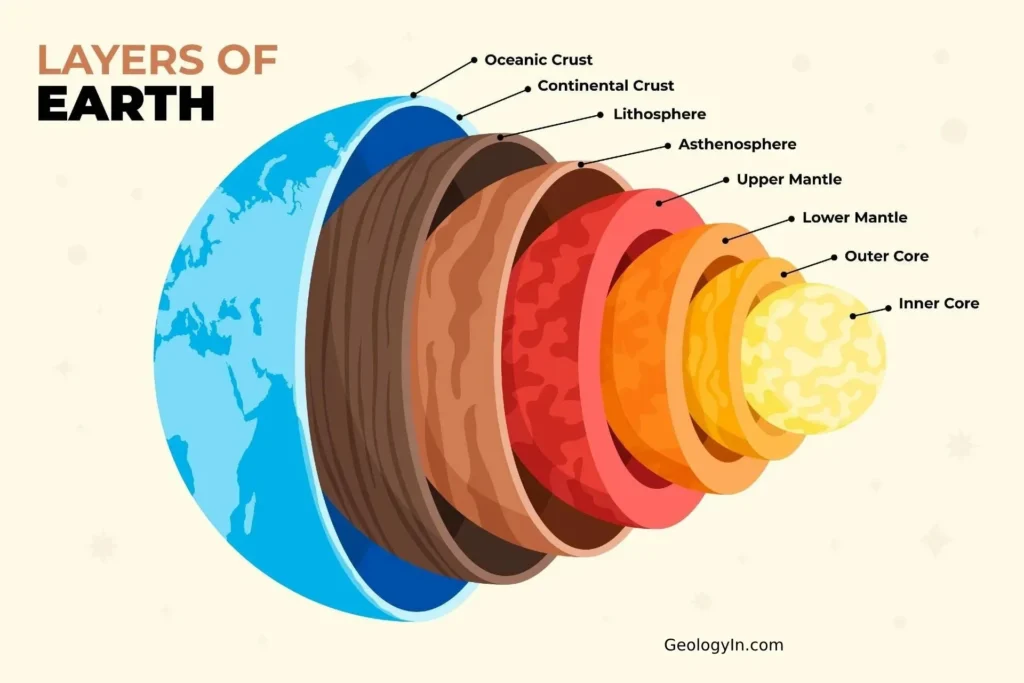

Earth’s internal composition reveals multiple layers distinguished by their chemical makeup and mechanical properties. These divisions classify the planet’s structure into the crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere, mantle, outer core, and inner core. While the outer core remains fluid, the rest including the partially molten asthenosphere exists in solid form. Variations in chemistry and physics across these layers stem from evolving gradients in temperature, pressure, and density over geological time.

Scientists infer Earth’s subsurface architecture from both direct observations and indirect indicators, notably seismic waves that refract uniquely through each layer according to its material and state.

Sources for the Interior of the Earth

Surface materials differ markedly from subsurface compositions, necessitating both direct and indirect approaches to probe Earth’s internal framework.

Direct Evidence:

- Mining: Minerals serve as primary accessible samples, extracted from depths reaching 3-4 km, such as South Africa’s gold mines.

- Drilling Initiatives: Ventures like the Deep Ocean Drilling Project and Integrated Ocean Drilling Program probe crustal conditions at greater depths.

- Volcanic Activity: Eruptions eject magma for lab scrutiny, though pinpointing its origin depth proves challenging.

Indirect Evidence:

- Thermal, Pressure, Density Profiles: Earth’s known radius enables modeled variations of these parameters by depth.

- Seismicity: P- and S-wave shadow zones reveal layer densities; S-waves’ inability to pass fluids confirms a molten outer core via abrupt disappearance zones.

- Seismic propagation speeds define discontinuities across layers.

- Gravity Variations: Latitude-based anomalies indicate subsurface mass distribution.

- Magnetic Mapping: Surveys trace crustal ferromagnetic material placement.

- Meteorites: Their composition and build mirror Earth’s interior, offering comparative insights.

Structure of the Earth

The planet comprises distinct concentric layers categorized by mechanical behavior and chemical makeup. Mechanically, these include the rigid lithosphere, ductile asthenosphere, solid lower mantle (or mesospheric mantle), liquid outer core, and solid inner core. In terms of composition, divisions align with the crust, mantle, and core.

Evolution of the Earth’s Layered Structure

Approximately 4.5 billion years ago, Earth emerged as a homogeneous sphere of incandescent rock, further intensified by residual heat from accretion and radioactive breakdown.

Iron Catastrophe: Roughly 500 million years later, temperatures surged to iron’s melting threshold (~1,538°C), termed the Iron Catastrophe, facilitating swift circulation of molten silicates and metals.

Layer Formation: Dense iron-nickel alloys sank to the planet’s core, while lighter silicates and volatiles rose outward, a phenomenon called planetary differentiation. The encircling melt evolved into the primordial mantle, with persistent liquid “incompatible elements” solidifying into the fragile crust, continually reshaped by plate tectonics.

Mantle Solidification: Bound water in minerals escaped as lava through outgassing, promoting progressive mantle cooling and hardening.

Thermal and Physical State of Earth’s Interior

Temperature, pressure, and density govern the Earth’s interior conditions.

Temperature: Observations from deep mines and wells show temperature increasing with depth. This is supported by molten lava from volcanic eruptions, indicating heat rises toward the core. The temperature gradient is not uniform: within the upper 100 km, it ranges from 15°C to 30°C per km.

It then lessens substantially through the mantle, rises sharply near the mantle’s base, then increases gradually through the core. Approximate temperatures are 1,000°C at the crust base, 3,500°C at the mantle base, and 5,000°C at the Earth’s center. Radioactive decay and high-pressure chemical reactions contribute to this intense internal heat.

Pressure: Due to the immense weight of overlying rocks, pressure increases steadily from surface to core, reaching around 3 to 4 million times atmospheric pressure at the center.

Density: Averaging 5.5 g/cm³ internally, density increases inward because of rising pressure and heavier material concentration toward the core.

Crust

- The outermost layer of Earth, the crust accounts for merely 1% of the planet’s mass yet harbors nearly all known life. Shaped by vigorous geological processes, it undergoes constant renewal through the planet’s dynamic motions and energies, primarily driven by plate tectonics that both creates and erodes crustal rocks.

- Composition: Comprising solid rocks and minerals, the crust features igneous (e.g., granite, basalt from cooled magma), metamorphic, and sedimentary varieties, with igneous rocks dominating.

- Density: Typically under 2.7 g/cm³.

- Types: Divided into oceanic crust (beneath oceans) and continental crust, the latter buoyantly rides higher on the mantle owing to its lower density.

- Discontinuity: Conrad discontinuity delineates the boundary between oceanic and continental crust.

Difference between Oceanic and Continental Crust

| Features | Oceanic Crust | Continental Crust |

| Composition | Mafic and ultramafic intrusive igneous rocks; mostly silicate and magnesium minerals (SiMa) | Granitic (felsic) intrusive igneous rocks; mostly silicate and aluminum minerals (SiAl) |

| Formation | Forms from magma rising from the mantle and cooling at the ocean floor | Forms from melting of rocks and accumulation of sediments |

| Mineralogy | Rich in iron and magnesium | Rich in silicon and oxygen |

| Thickness | Typically about 5-10 kilometers | Can be up to 40 kilometers thick |

| Density | Approximately 2.9 grams per cubic centimeter | Approximately 2.7 grams per cubic centimeter |

Mantle

- The Earth’s mantle is a thick layer approximately 2,900 km deep, situated between the dense core and the outer crust. It makes up about 84% of Earth’s volume and 67% of its mass.

- The mantle’s density averages around 3.9 g/cm³, increasing with depth. It primarily consists of silicate minerals including olivine, garnet, and pyroxene, with significant amounts of magnesium oxide. Other elements present are aluminum, iron, calcium, sodium, and potassium.

- The boundary between the crust and mantle is marked by the Mohorovicic Discontinuity (Moho), where a sharp density contrast causes an increase in seismic wave velocities.

- This layer behaves mostly as solid rock but over geological time scales can flow slowly, enabling mantle convection which drives plate tectonics.

Layers of Mantle

- The Earth’s mantle primarily splits into the upper mantle and lower mantle, separated by the Repetti Discontinuity.

- Upper Mantle: Though largely solid, its pliable zones drive tectonic movements; it spans roughly 410 km thick and includes the rigid lithosphere and underlying asthenosphere.

- Transition Zone: Spanning 410-660 km depths, this layer limits major material exchange between upper and lower mantle; notably, its minerals trap water volumes equivalent to Earth’s surface oceans.

- Lower Mantle: Extends from ~660 km to 2,700 km, exhibiting higher temperatures and density than the upper mantle.

- D” Layer (D-double prime): A basal zone under the lower mantle, featuring thin outer core contacts in places and thicker iron-silicate piles elsewhere.

Lithosphere

It is the solid, outer part of Earth. It is made up of the crust and the upper mantle, above the asthenosphere. Of all the layers of the Earth, the lithosphere is both the coolest and the most rigid.

- Thickness: The average thickness of the lithosphere is 100 km and may go up to 300 km below the orogenic mountains.

- The thickness of the lithosphere is less than 50 km below the oceanic crust.

- Composition: The lithosphere consists of many different large segments or blocks, called lithospheric plates or tectonic plates.

- These plates are considered rigid bodies floating horizontally over the asthenosphere, and tectonic deformations typically occur at the plate boundaries as a result of plate interactions with other plates.

Asthenosphere

The asthenosphere is a hot, soft, mechanically weak, ductile and semi-viscous region and consists of semi-molten rock materials.

- Properties: The Asthenosphere is part of the upper mantle also known as the Low-Velocity Zone (LVZ) because the velocity of seismic waves decreases in this zone.

- This zone allows the lithospheric plate to float and move over it.

- Thickness: The average thickness is between 180 to 220 km.

- Depth: It lies below the lithosphere at an average depth of 100 km and extends to a depth of 350 to 650 km.

- Composition: It is composed of peridotite rock, containing mostly the olivine and pyroxene minerals.

Core

The extremely hot and dense center of our planet is known as the Earth’s core. The Gutenberg discontinuity signals the end of the mantle and the commencement of Earth’s liquid outer core.

- Volume: The core accounts for 33% of the Earth’s mass and 16 percent of the Earth’s volume.

- Composition: Unlike the mineral-rich mantle and crust, it is made almost entirely of metal – iron (Fe) and nickel (Ni) hence, sometimes called NiFe layer.

- Siderophiles, the elements that dissolve in iron (gold, platinum, cobalt, etc) are also found in the core.

- The core contains 90% of the earth’s sulfur.

- The other elements speculated to be the parts of the core are oxygen and silicon.

- Two layers: The core is further divided into two layers – inner core and outer core. The Lehmann discontinuity or the Bullen discontinuity is the boundary separating these regions.

Outer Core

The 2,200 km thick outer core is composed of liquid iron and nickel, in a molten state.

- Properties: The hottest part of the core (at the Bullen discontinuity) is as hot as the surface of the sun (around 6,000° Celsius).

- The liquid metal in the outer core has low viscosity.

- Earth’s magnetic field: The Earth’s magnetic field is created in the outer core by a self-exciting dynamo process.

- The magnetic field is generated by electrical currents flowing through slow-moving molten iron.

Inner core

Earth’s inner core is solid and extends from 5150 Km to 6370 Km, and is mostly composed of iron.

- Solid core: Despite the temperature of the inner core being more than the melting point of iron, the inner core is solid.

- This is due to the intense pressure and density of the inner core.

- Rotation: The inner core rotates eastward but at a little faster rate than the other part of the Earth.

- Growth: The inner core grows by about a millimeter every year as the Earth is slowly cooling.

- Consequently, the outer core is solidifying or freezing.

FAQs

Q1. How do scientists study the interior of the Earth?

Scientists study the Earth’s interior mainly through seismic waves, volcanic eruptions, gravity measurements, magnetic surveys, and meteoritic evidence.

Q2. What are seismic waves, and why are they important?

Seismic waves are vibrations produced during earthquakes. Their speed and behavior help scientists determine the state, density, and composition of Earth’s internal layers.

Q3. 4. What are the main layers of the Earth?

The Earth has three major layers:

Core (innermost, divided into outer and inner core)

Crust (outermost)

Mantle (middle layer)

Q4. What is the difference between continental and oceanic crust?

Continental crust: Thick (35–70 km), lighter, granitic in composition.

Oceanic crust: Thin (5–10 km), denser, basaltic in composition.

Q5. What is the asthenosphere?

The asthenosphere is a semi-molten, ductile layer in the upper mantle below the lithosphere. It allows the movement of tectonic plates.

Click on the question to see the Answers