The Revolt Of 1857, Modern History

Content

- Introduction

- Reasons Behind the Revolt of 1857

- Revolt of 1857 Timeline

- Revolt of 1857 Leaders

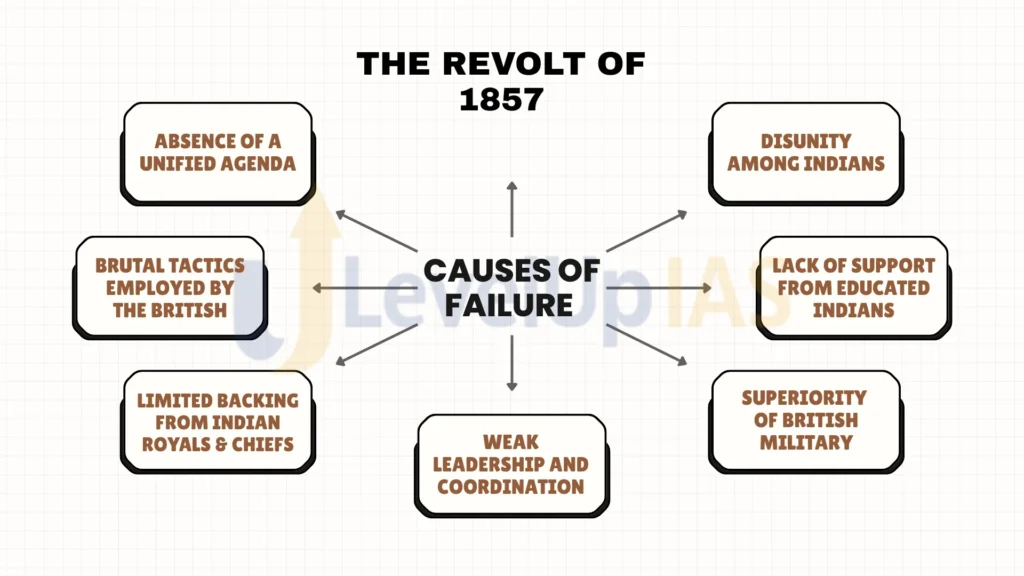

- Causes of Failure of the Revolt

- Consequences of the Revolt

- Revolt of 1857 Features

- FAQs

Introduction

The Revolt of 1857 is referred to as the “First War of Independence.” It marked the first major effort by Indians to resist British colonial rule. It began on 10 May 1857, initially as a mutiny among sepoys. And eventually evolved into a united effort led by Indian rulers under the official oversight of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. Since the Revolt of 1857 represented a significant threat to British authority, it served as a pivotal moment that altered the British view on governance in India. They adopted a more cautious strategy regarding administration, military composition, and the diverse treatment of the large Indian population.

The Revolt of 1857 saw a concentration of action across northern India. That involved both the peasantry and other civilian groups who joined forces with their leaders. Numerous prominent figures of the Revolt, along with the common people, courageously confronted British troops.

Reasons Behind the Revolt of 1857

Multiple factors contributed to the Revolt of 1857, although the British’s harsh exploitation of the Indian populace was a common thread. These issues had been intensifying since the consolidation of Bengal in 1764. Which led to various smaller uprisings and finally culminating in the Revolt of 1857. The following factors summarize the causes:

Political Factors of the Revolt of 1857

Widespread dissatisfaction with British political policies drove the Revolt of 1857. That undermined the authority and traditions of Indian leaders. These measures not only alienated the ruling class but also disrupted the social and political structure of Indian society. Which ignited widespread anger. Significant political causes include:

- Doctrine of Lapse: Lord Dalhousie introduced this policy and annexed territories without direct heirs. Such as Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur.

- Annexation of Awadh: In 1856, the British annexed Awadh on the pretext of “misgovernance,” which fueled local discontent.

- Disrespect towards Rulers: Indian monarchs were stripped of their powers. Bahadur Shah II faced humiliation as Britishers excluded his heirs from the Red Fort.

- Loss of Privileges: Numerous landholders, zamindars, and princes had their estates taken away, leading to the alienation of the elite class.

- Exclusion from Key Positions: The British barred Indians from obtaining important civil and military positions. It caused frustration among the educated and ruling elites.

- Diminution of Local Authority: British policies undermined the influence of chieftains and tribal leaders, inciting further unrest.

Economic Causes of 1857 Revolt

The economic strategies employed by the British resulted in extensive poverty and discontent among Indians. Which played a significant role in the emergence of the Revolt of 1857. These strategies disrupted established economic frameworks and favored the British at the cost of the local populace. The main economic factors include:

- Wealth Extraction: The British extracted resources to support their empire. And used Indian revenues to finance governance and military operations overseas.

- Taxation Policies: High taxes imposed under the Permanent Settlement, Mahalwari, and Ryotwari systems led to the loss of land and suffering among farmers.

- Destruction of Local Industries: The influx of British manufactured goods devastated traditional crafts. It left many artisans unemployed and making India reliant on British imports.

- Agricultural Exploitation: The enforced cultivation of cash crops like indigo and opium resulted in famines and food shortages, severely oppressing indigo farmers.

- Erosion of the Aristocracy: British reforms displaced zamindars, creating instability and fostering resentment.

- Widespread Hardship: Traditional laborers experienced unemployment as British products flooded the market, exacerbating distress in both rural and urban areas.

- Famine: The focus on cash crops and high taxes led to food shortages and recurrent famines.

Social Causes of Revolt of 1857

Pervasive social unrest across various segments of Indian society drove the Revolt of 1857. British policies and reforms disrupted longstanding traditions, social hierarchies, and religious practices. That fostered a profound sense of alienation and animosity towards colonial rule.

- Racial Discrimination: The British upheld a sense of racial superiority, treating Indians, including those from elite backgrounds, with disdain.

- Religious Interference: British reforms challenged long-standing customs. Such as the banning of Sati and the legalization of widow remarriage, alienating conservative factions.

- Missionary Activities: Intense efforts from Christian missionaries incited fears of religious conversion among Hindus and Muslims.

- Alien Rule: The British maintained a social distance, failing to integrate with Indian society, which intensified feelings of resentment.

- Erosion of Religious and Social Prestige: Religious leaders such as Pandits and Maulvis saw their traditional authoritative roles diminished under British authority.

- Destabilization of Social Order: Reforms like the land revenue policies and Doctrine of Lapse disrupted established power dynamics, leading to societal instability.

Administrative Factors of Revolt 1857

The discontent stemming from British administrative practices played a crucial role in the revolt’s origins. Key administrative issues are outlined as follows:

- Centralized Authority: The British centralized power, diminishing the authority of local rulers and chieftains. Which bred resentment among traditional elites.

- Land Revenue Systems: The British enforced exploitative land revenue structures like the Permanent Settlement and Ryotwari system. Which was placing heavy tax burdens on peasants and causing widespread economic suffering.

- Cultural Insensitivity: British legislation and policies were perceived as dismissive of Indian traditions and customs. It included attempts to impose Western education and legal frameworks, which distanced them from the Indian populace.

- Military Discontent: The notable recruitment practices, poor treatment, and limited advancement opportunities for Indian soldiers in the British military generated substantial dissatisfaction.

Immediate Cause of Revolt of 1857

The immediate trigger for the Revolt of 1857 was the introduction of the Enfield Rifle. Its associated greased cartridges were widely believed to be smeared with animal fat, particularly from cows and pigs. This incited considerable outrage among Hindu and Muslim soldiers who perceived a violation of their religious principles.

- The soldiers’ refusal to use these cartridges ignited a rebellion among the sepoys, especially in Meerut, which rapidly spread to various regions of India, leading to the revolt

Revolt of 1857 Timeline

The Revolt of 1857 was marked by a series of significant events. It was initially confined to military uprisings but was soon transformed into a widespread insurrection. Beginning with Mangal Pandey’s act of defiance at Barrackpore, extensive uprisings were witnessed across North and Central India. This timeline highlights the pivotal events, actions, and consequences that shaped the uprising.

| Date | Event |

| 29 March 1857 | Mangal Pandey’s Revolt: Mangal Pandey, a sepoy posted at Barrackpore, openly defies British officers. He is later arrested and executed by hanging. |

| 24 April 1857 | Meerut Incident: Ninety soldiers of the Third Native Cavalry refuse to use cartridges believed to be greased, resulting in their dismissal from service. |

| 9 May 1857 | Punishment of Sepoys: A total of 85 sepoys are sentenced to imprisonment, an action that significantly intensifies discontent within the army ranks. |

| 10 May 1857 | Outbreak at Meerut: The sepoys stationed at Meerut rise in rebellion, release their imprisoned comrades, kill British officers, and advance towards Delhi. |

| May 1857 | Advance to Delhi: The rebelling sepoys, joined by sections of the civilian population, proceed to Delhi and proclaim Bahadur Shah II as the Emperor of India. |

| June 1857 | Role of Nana Saheb: Nana Saheb assumes leadership of the revolt in Kanpur, captures British officers, and declares himself the Peshwa. |

| June–July 1857 | Spread of the Revolt: The uprising expands across large parts of North India, with significant centres of resistance emerging in Lucknow and Cawnpore. |

| August 1857 | Events at Gwalior: Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, along with Tatya Tope, makes an attempt to seize control of Gwalior from British forces. |

| September 1857 | Siege of Delhi: British forces initiate a siege of Delhi in an effort to re-establish authority following the sepoy-led uprising. |

| March 1858 | Suppression Phase: British troops under General Havelock recapture Cawnpore, and the revolt is subdued in most parts of the country. |

| 1858 | Formal End of the Revolt: The British officially put an end to the rebellion, leading to the dissolution of the East India Company and the beginning of direct British Crown rule in India. |

Revolt of 1857 Leaders

The main hubs of the rebellion were situated in Arrah, Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Bareilly, and Lucknow. Despite recognizing Emperor Bahadur Shah’s authority, each of these areas chose their own leaders and maintained their independence.

| Leader | Contribution |

| Bakht Khan (Delhi) | After reaching Delhi from Bareilly, Bakht Khan effectively assumed actual authority in the city. He organised a Court composed of soldiers belonging to both Hindu and Muslim communities, thereby giving structured leadership to the rebellion in Delhi. |

| Begum Hazrat Mahal (Lucknow) | She declared her son as the Nawab of Awadh and played a decisive leadership role in Lucknow .Maulavi Ahmadullah supported her efforts and emerged as a highly influential and popular leader of the rebel forces. |

| Rani Lakshmi Bai (Jhansi) | She led the rebel forces in Bundelkhand and put up a courageous resistance against the British troops commanded by Hugh Rose. Later, she joined hands with Tatya Tope in an attempt to recapture Gwalior from British control. |

| Nana Saheb (Kanpur) | Nana Saheb headed the uprising at Kanpur, where he successfully defeated British forces led by Hugh Wheeler. After driving the British out, he proclaimed himself the Peshwa, reviving Maratha political symbolism. |

| Kunwar Singh (Bihar) | He spearheaded the rebellion in Bihar and parts of central India. Kunwar Singh inflicted a significant defeat on British forces at Arrah but later succumbed to injuries in 1858. |

| Tatya Tope (Kanpur & Gwalior) | Known for his effective use of guerrilla warfare, Tatya Tope captured Kanpur on behalf of Nana Saheb. Following the British recapture of Kanpur, he withdrew towards Gwalior to continue resistance. |

Causes of Failure of the 1857 Revolt

Various internal and external factors led to the failure of the 1857 Revolt. Key issues such as the insurgents’ lack of unity, poor leadership, and insufficient support from significant segments of Indian society, contributed to its collapse. The primary reasons for its unsuccessful outcome are outlined below:

- Absence of a Unified Agenda and Ideology: The uprising did not present a definitive plan for governance, concentrating only on the expulsion of British rule, resulting in chaos and a deficiency in coordinated actions.

- Disunity Among Indians: The insurrection was not widespread, as areas such as Punjab and the south remained loyal to the British. Furthermore, differing local interests fueled divisions between Hindus and Muslims.

- Lack of Support from Educated Indians: The educated populace did not back the revolt, perceiving it as regressive and believing British rule was essential for modernization.

- Superiority of British Military Forces: The British troops were technologically advanced and better organized, equipped with superior artillery and aided by Indian rulers, ensuring their triumph.

- Weak Leadership and Coordination: The insurrection suffered from a lack of centralized leadership and coordination, with local leaders like Rani Lakshmibai and Nana Saheb not coming together under a single command.

- Limited Backing from Indian Royals and Chiefs: Numerous Indian monarchs aligned with the British, diminishing the revolt’s strength, as some had personal stakes in preserving British authority.

- Brutal Tactics Employed by the British: The British reacted with extreme measures, such as reprisals, executions, and severe punishments, which deterred additional revolts and suppressed the uprising.

Consequences of the 1857 Revolt

The 1857 Revolt resulted in significant repercussions that transformed India’s political and social framework. Notable changes included reforms in military organization, alterations in political governance, and the adoption of a “divide and rule” strategy.

- Reforms in Military Structure: The British increased the number of European troops and reorganized Indian regiments to obstruct unity among soldiers. The British structured regiments based on caste, community, and region to suppress nationalist sentiments.

- Transfer of Authority: The control of India transitioned from the East India Company to the British Crown via the Government of India Act of 1858. A Secretary of State for India, assisted by a Council, assumed responsibility.

- “Divide and Rule” Policy: The British exacerbated divisions among Indians, particularly by favoring discrimination against Muslims in public appointments, which later fostered communal tensions and impeded the struggle for freedom.

- New Strategy Regarding Princely States: The British replaced the policy of annexation with one that allowed princely rulers to adopt heirs, restoring some degree of autonomy to local leaders.

Revolt of 1857 Features

The Revolt of 1857, often referred to as the First War of Indian Independence, was a pivotal event that initiated organized resistance against British colonial dominance in India. This event represented a crucial moment in the history of the Indian subcontinent. Which led to significant political, social, and military repercussions. The following points outline the characteristics of the revolt and its influence on India’s historical narrative:

- Geographical Reach: The uprising extended across extensive regions of northern, central, and western India, including major cities such as Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, and Meerut. However, it was less prominent in the southern and eastern parts of the country.

- Varied Involvement: The revolt involved a wide range of Indian society members, including soldiers (sepoys), farmers, craftsmen, landlords, and even leaders like Rani Lakshmi Bai, Begum Hazrat Mahal, and Nana Saheb.

- Religious and Social Cohesion: The uprising featured Hindu-Muslim unity, as individuals from both faiths came together to resist British authority. Bahadur Shah II, a Mughal emperor, was proclaimed the symbolic leader, symbolizing a nascent collective Indian identity.

- Military Insurrection and Civil Disturbance: Although sepoys in the British East India Company’s forces started the rebellion, it quickly evolved into a widespread civilian uprising, with towns and villages across India participating.

- Opposition to British Policies: Various grievances fueled the revolt, including annexation policies (Doctrine of Lapse), heavy taxation, cultural insensitivity, religious interference, and the controversial introduction of military practices like the greased cartridge.

- Absence of Central Coordination: In spite of initial victories, the revolt suffered from a lack of central leadership, strategy, and coordination, resulting in fragmentation and eventual defeat.

- Cruel British Repression: The British forces reacted with harsh reprisals, including mass executions, torture, and the annihilation of towns, which in turn heightened Indian animosity.

- Enduring Legacy of Nationalism: Although the revolt ultimately failed, it planted the seeds of nationalism, inspiring future generations of Indians to unite in their quest for independence from British rule.

FAQs

Q1. What was the Revolt of 1857?

The Revolt of 1857 was a widespread uprising against British East India Company rule, beginning with a sepoy mutiny at Meerut and later spreading across northern and central India.

Q2. Why is the Revolt of 1857 called the First War of Indian Independence?

It is termed so because, for the first time, diverse sections of Indian society, sepoys, peasants, rulers, and civilians, collectively challenged British authority on a large scale.

Q3. What were the main causes of the Revolt of 1857?

A combination of political annexations (Doctrine of Lapse), economic exploitation, military grievances, religious interference, and racial discrimination by the British caused the revolt.

Q4. Who were the major leaders of the Revolt of 1857?

Key leaders included Bahadur Shah Zafar (Delhi), Rani Lakshmibai (Jhansi), Nana Saheb (Kanpur), Kunwar Singh (Bihar), Begum Hazrat Mahal (Lucknow), and Bakht Khan (Delhi).

Q5. Why did the Revolt of 1857 fail?

The revolt failed due to lack of unified leadership, limited geographical spread, poor coordination, absence of modern weapons, and superior British military organisation.

Click on the question to see the Answers